“Dietary Guidelines” by committee.

Nutrition is complex. So is the human body. Everyone is different with widely diverse personal circumstances. So, do “one-size-fits-all” nutrition guidelines made by committee a good idea?

Trust is a food ingredient.

When a mom places food on the plates of her children, or packs a lunch bag for school, she has generally sourced the food from a grocery store or food market.

Mom believes the food to be safe. She knows that regulatory agencies exist to protect consumers like her and her family from dangerous products. She trusts them.

However, who are the people making the regulations? What qualifies them to make those decisions? How were they selected for that responsibility? How, and by whom, are those regulations enforced? How effective are their enforcement measures?

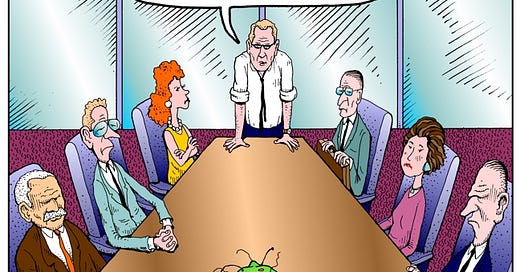

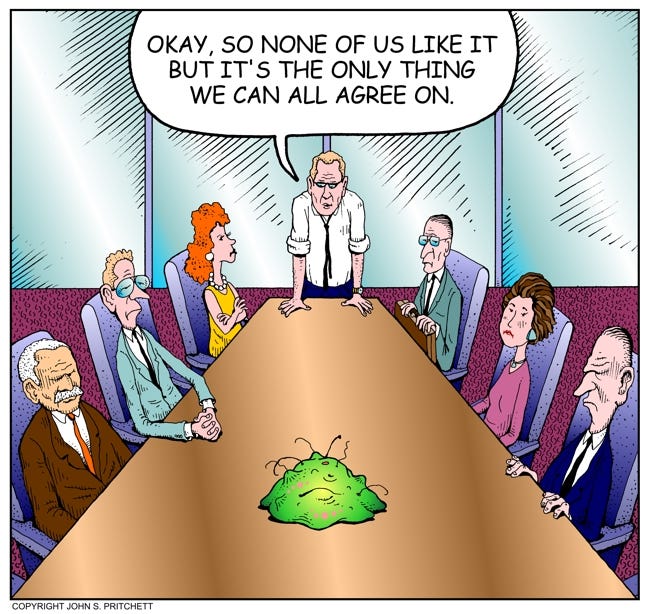

Anyone who has spent time in a decision-making body knows that they are not perfect. Perhaps your experience includes being a member of City Council, or as a School Trustee, or a Board member at your local golf club, or you were elected to the Executive Committee of a political party. In all cases, every committee member possesses a unique life lens which leads him or her to believe what’s important and what should be a priority. Sometimes the members agree, and sometimes they don’t.

Now imagine the people, processes and circumstances that go into the creation of the Dietary Guidelines for America, and the equivalent for Canadians.

This article from The Epoch Times will help you to imagine how Dietary Guidelines are created. It doesn’t answer the questions I posed above, but it does provide a glimpse into the process. I clipped three paragraphs from it to whet your appetite to consume the whole enchilada.

From Food Pyramid to Flawed Policy

For decades, the Dietary Guidelines have shaped how Americans eat, but their legacy is marked by controversy. Introduced in 1980, they shifted focus from overall nutrition to targeting fat intake, blaming dietary fat for heart disease and urging Americans to swap butter for margarine and adopt low-fat, high-carbohydrate diets.

Before the 1980 guidelines, Americans consumed about 45 percent of their calories from fat. The new recommendations reduced this to 30 percent while encouraging carbohydrates to make up 55 to 60 percent of daily calories—primarily from grains. This shift became the foundation for the now-debated food pyramid of the 1990s, emphasizing grains as the base of a healthy diet.

In response, food manufacturers reformulated products to align with the low-fat guidance, often adding sugar and refined grains to maintain flavor and appeal—a phenomenon dubbed the “Snackwell Effect,” referring to the rise of low-fat but highly processed snack foods. These changes fuelled the increased consumption of processed foods, indirectly supporting trends that some researchers now link to rising rates of obesity and diabetes.

Personal Knowledge is best.

Not everyone knows as much about nutrition as my daughter. She graduated top of her class with a Bachelor of Applied Science in Dietetics and she applies her training every work day as a ward Dietician in a major hospital. Her young son, my grandson, gets the benefits of all her training and you can bet that Canada’s Food Guide is not her sole source of information concerning diet and nutrition.

Relying on your doctor is likely not your best source for dietary advice. Most family physicians will admit that they received very little nutrition training in medical school.

As Peter Attia MD stated recently in a podcast, “The two main tools that doctors are trained to use are a scalpel and a prescription pad”. His book, Outlive: The Science & Art of Longevity, is a good place to start for anyone interested in attaining and maintaining good health, including dietary advice. I am a big fan of his The Drive podcast series.

Today, expert knowledge about nutrition comes largely from outside of the medical profession. It can be obtained from some institutions as well as private practitioners with a wide range of training and expertise. For example, one person I know, a retired public school teacher, calls herself a Nutrition Consultant while selling only the products of a large American corporation that operates a multi-level marketing business. She earns commissions on sales and claims to only trust the doctors employed by the company and the product-related science they publish.

Another friend is a former scientist and University Professor with a PhD in Physiology. She currently operates a Holistic Health and Nutrition practice in South-Western Ontario. As an active member of the Canadian Citizens Care Alliance, she is also well-connected to the CCCA’s network of hundreds of research scientists, medical doctors and healthcare practitioners across Canada.

My point is…

There are many sources of nutrition information available today besides the Canadian Food Guide. Each offers different products and services that cater to a wide variety of needs.

Good nutritional health depends on good information provided by trustworthy sources.

The onus is on each individual to acquire the knowledge to make the best choices from the range of options available.

We only have one body, and we are the sole custodian of it. Maintain it or lose it.

The choice is clear. We can outsource our nutrition knowledge to committees of strangers who write the Canadian Food Guide, OR we can seek out and find the best sources the broader market of options has to provide. Persistence and due diligence is how to find trustworthy sources.

Excellent post, important subject.

I like the way you connect the personal to the general message.

Wait a second.... that's what I do too 😀!!